QRHC Part 1: A Nano-cap Sustainability Play

An asset-light waste management service is set to deliver triple-digit earnings growth by helping corporations reduce waste and improve recycling

Welcome to Efficiencies, a blog situated at the intersection of strategy and sustainability, exploring all that relates to the business models and industry dynamics of the disruptors and the disruptees in our shift to the Green Economy. If you like what you read, please show your support with a free subscription or by sharing with a friend! Join the discussion and let’s grow this community.

Though I believe that sustainability will be a major business theme for our generation, it isn’t an easy theme to invest in. So when I stumbled upon what appears to be a secular inflection in demand for recycled plastics, I hoped, for a brief moment, to profit from this insight until I recalled from part 1 of the recycling series that the major waste companies restructured their recycling contracts to pass through recycled commodity price volatility to their customers after prices cratered in the wake of China’s 2018 ban. This vote of no confidence in sustainability left these companies on the sidelines after exiting at the trough. They are, as a good friend and analyst who attended ESG meetings with their management teams put it, “total weenies.”

A Mismatch in Incentives

Waste management companies’ economic incentives are not aligned with recycling; landfills and the supporting infrastructure (collections and transfer stations) represent the bulk of their investments and their highest margin income. Waste Management lays out why reduced trash – through recycling, reduction or composting – is a risk to their business:

“Our customers are increasingly diverting waste to alternatives to landfill disposal, such as recycling and composting, while also working to reduce the amount of waste they generate. In addition, many state and local governments mandate diversion, recycling and waste reduction at the source and prohibit the disposal of certain types of waste, such as yard waste, food waste and electronics at landfills. Where such organic waste is not banned from the landfill, some large customers such as grocery stores and restaurants are choosing to divert their organic waste from landfills. Zero-waste goals (sending no waste to the landfill) have been set by many of the U.S. and Canada’s largest companies. Although such mandates and initiatives help to protect our environment, these developments reduce the volume of waste going to our landfills which may affect the prices that we can charge for landfill disposal. Our landfills currently provide our highest income from operations margins. If we are not successful in expanding our service offerings, growing lines of businesses to service waste streams that do not go to landfills providing services for customers that wish to reduce waste entirely, then our revenues and operating results may decline. Additionally, despite the development of new service offerings and lines of business, it is possible that our revenues and our income from operations margins could be negatively affected due to disposal alternatives.”

Revenues for integrated waste companies are driven by waste volume and collection & disposal prices. Prices charged at disposal facilities, referred to as tipping fees, are based on the expected lifetime cost of the landfill and the distance to a competing disposal facility. Profitability is influenced by how much of the trash from the company’s collections operation is sent to its own disposal facilities (like landfills), a practice referred to as internalization. The obvious strategy here for a profit-maximizing firm is to consolidate landfills, raise prices, and collect as much trash as possible, which is exactly what Waste Management has done.

Now consider the customer’s perspective. Disposal costs are increasing – despite lower YoY volumes, prices in Q1 increased between 3.2-3.5% for the major solid waste companies and CEOs across the board are bullish on further price gains. At the same time, recycling and other disposal alternatives, driven by higher commodity prices, legislative action & sustainability commitments and technological improvements, are increasingly attractive from an economic and social standpoint. There’s a mismatch in incentives here, which creates space for an alternative business model and potential investment.

Quest Resource Holding Corporation (NASDAQ:QRHC)

Note: The following is not investment advice. I have a position. Do your own work. This write-up is split into two parts. Part 1 covers the business model and explores the value chains for key waste streams. Part 2 will dig into financials, forecasts, valuation, etc.

Enter Quest Resource Holding Corporation, an asset-light waste and recycling services company that designs and manages solutions to minimize waste costs and realize the commodity value of recyclables for commercial customers in retail/grocery, automotive, industrial, restaurants and multifamily housing.

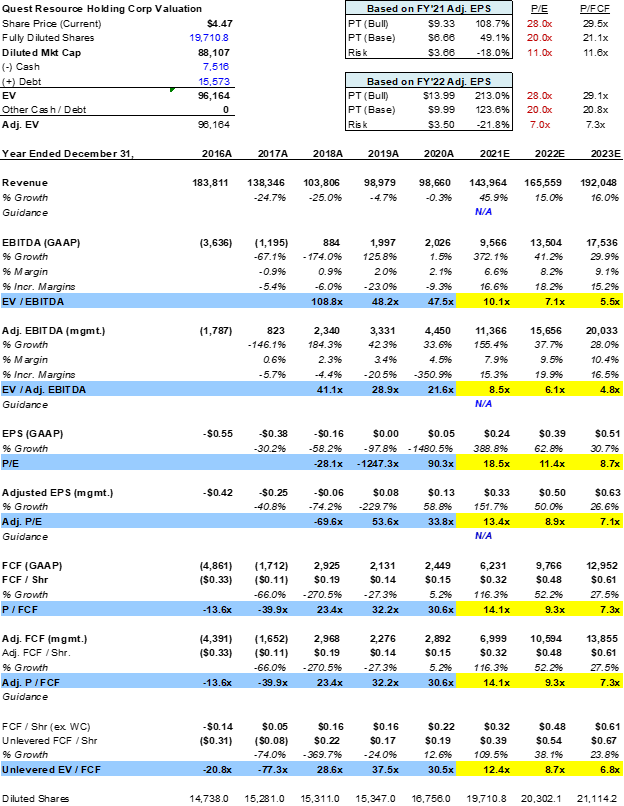

This company is a unique case study in preparation meeting opportunity. Its business model is better aligned with its customers interest and is disposal agnostic at a time when (1) large corporations are becoming more thoughtful about waste and disposal and (2) disposal and recycling are becoming more specialized. It is also coming into this opportunity from a turnaround that masked accelerating organic growth and (necessarily) de-levered operating expenses. With the turnaround and COVID now behind Quest, this $77m market cap company is signing seven figure contracts with Fortune 1000 businesses, expanding with existing customers and re-leveraging its operating expenses. For the numerically inclined, this means double digit top-line growth, >600 bps margin expansion and a triple digit CAGR in operating income and earnings for the modest cost of 13x FY21 earnings. I value QRHC at $8-$10 a share, offering upside of 79% - 124%.

Business Overview

Complexity is the chief obstacle to waste reduction; proper disposal & recycling requires sorting and segmenting our waste into smaller, homogenous streams. However, managing the complexity of multiple waste streams presents formidable challenges for both waste generators and disposal & recycling (D&R) businesses. For a business, internally managing multiple waste streams is a logistical nightmare. A grocery store can send its food waste, for example, to composters, waste to energy plants or animal feed producers. Waste management is highly local; for a grocery store chain, the most cost-effective disposal method will vary from store to store depending on what is nearby. On the other side of the exchange, landfill alternatives are capital intensive, low margin businesses who depend on sourcing sufficient volume of a specific type of waste, which may or may not have well established collection infrastructure.

Quest solves these pain points for both waste generators and D&R businesses. Quest manages multiple waste streams at the local level for waste generators, acting as the single point of contact between a business and its network of 3,500+ vendors. For D&R businesses, it aggregates volume and reduces friction in the market while leveraging that volume to get achieve better pricing for its customers. Quest is arguably a platform business for waste management - not nearly as sexy as Amazon, but a platform business nonetheless.

Quest assesses clients current waste generation, identifies opportunities for reduction and diversion, designs custom solutions and, most importantly, provides auditable data reporting through its business intelligence platform that clients can use in CSR, Sustainability and ESG reporting. Management provides a few instructive examples in their presentations:

Auditable data reporting is a valuable service for customers looking to meet sustainability goals. As CEO Ray Hatch explained in the Q3 2019 earnings call,

“I would say a couple of years ago, it was more about getting the job done. But just maybe 3 or 4 years ago, it's increasingly more and more important to these companies that they have credible reporting on their ESG reporting. And credible, obviously goes back to collecting the data in a timely, accurate manner and giving it back to them in a way that they can divulge it appropriately.

But we're hearing that a lot, Nelson. I mean, we just had a meeting recently with another large corporate manufacturer brand that's looking for answers. And they're almost predominantly around diversion and things that's going to help their environmental scores. And it's given that on top of that, they also want to save money. That's -- I want to leave that out there. It's always part of the equation. But it's becoming more and more prominent.”

This sentiment mirrors trends seen in studies of companies in the Russell 1000. The Governance and Accountability Institute, a consulting and research firm, found that the percentage of companies publishing sustainability reports increased to 65% in 2019 from 60% in 2018, with 90% of the largest 500 companies and 39% of the 500 smallest companies publishing reports. These companies make up Quest’s growing customer base:

The Waste Ecosystems and Their Value Proposition

Corporate goodwill on its own isn’t an investment thesis. Although more companies are setting targets and publishing reports than ever, most are on track to miss their self-imposed targets. Part of this comes down to a lack of rigorous analysis on the part of management, but I suspect management teams are unrealistically optimistic about their (or their industry’s) willingness to sacrifice short term profitability without regulatory sticks jabbing them forward. Cost matters. What’s special about Quest is that its solutions facilitate both sustainability and cost efficiency.

Waste management has two cost components: collection and disposal a.k.a. tipping fees. Collection is the cost to transport waste to its ultimate destination. This cost is scalable on a per-ton basis based on the density of the collection route and distance to disposal. Tipping fees are the cost to store the waste in a landfill or other disposal facility. In 2019, the national average tipping fee for landfills was $55.36 per ton. Assuming you have a landfill and an alternative disposal facility side by side with the same collection cost, the disposal facility needs a tipping fee below $55 to compete with the landfill.

The primary waste streams that Quest handles are used oil, oil filters, scrap tires, grease and cooking oil, solid waste, expired food, metals, cardboard and hazardous materials. These waste streams fall into one of two camps. In one camp are commodities like oil and metals with large, established markets and efficient recycling technology. Commercial Metals Company (NYSE:CMC) and Clean Harbors (NYSE:CLH) are publicly traded recyclers of steel and motor oil. Recyclers are a spread business, purchasing waste material, refining it and reselling it. In this case the tipping fee is a source of revenue to the customer, so you can have some massive disynergies in collection infrastructure and still be a superior alternative to the landfill. Despite the economic proposition, these landfill alternatives aren’t necessarily widely used:

“Just 1 percent of shop owners in the National Oil and Lube operator survey were paid for their waste oil in 2017. A year later, 28 percent reported getting paid, and there was a correlating drop in the number of shops paying for disposal. The survey also showed that more shop owners are neutral on waste oil — neither getting paid nor paying for disposal.

The changing market makes the re-refining an engaging line of work for people like Jim Scott.

Scott is the vice president of supply chains for Universal Environmental Services, a re-refiner based in Peachtree City, Ga. Whatever the price pressures are, the re-refinery business touts itself as the environmentally sound option, because it reduces reliance on crude oil.

“If we look at it like this: It takes 42 gallons of crude oil but only 1 gallon of used oil to produce 2.5 quarts of new lubricating oil,” Scott says.

The company’s re-refinery can process 40 million gallons of waste motor oil annually, and a lot of that comes from quick lube shops. They take oil filters, too, which can be crushed and sent to steel recyclers.”

I would guess that the recycling market, being low-margin and highly fragmented, has done a poor job of raising awareness amongst waste generators that they could be saving money by selling their commodity waste. I also suspect that some waste generators would rather pay to dispose of their waste in one stream rather than manage valuable waste streams separately. This is the problem Quest addresses – it brings awareness to disposal alternatives and manages the added complexity of separating waste streams.

Food Waste

In the second camp are waste materials whose disposal alternatives are just approaching cost competitiveness with landfills and thus have less established market infrastructure. Although food waste is far from the only waste stream in this category, I’ll focus on it as a representative example since grocery/retail and restaurants are major verticals for Quest. From the Q4 2020 earnings call:

“We also had a 7-figure win to expand our food waste program with existing clients. Our food waste diversion programs are growing -- are a growing category for a number of reasons. Sustainability concerns for both consumers and investors are putting pressure on grocery and restaurant chains to divert more and more waste -- food waste from the landfill. However, these low margin businesses, as you might expect, the incremental cost of these programs has kept the adoption of food waste programs from being totally widespread. However, with increases to landfill waste -- landfill costs, this may be changing. Most landfill operators have been and continue to implement price increases. This is good for our food waste program because in many areas food waste is now not only more environmentally attainable and sustainable, but it's becoming more economically attractive as well.”

What Ray doesn’t explain is that food waste programs are an incremental expense because the infrastructure to handle this waste is underdeveloped – so underdeveloped that just researching the various disposal businesses was a challenge. It’s the same chicken or the egg dilemma facing electric vehicle charging infrastructure in the EVGO series. Waste generators don’t want to sign onto a food waste program because the infrastructure (and therefore economics) isn’t there; Investors don’t want to build out the infrastructure because the committed volume isn’t there.

Food waste can be composted, anaerobically digested, combusted or turned into animal feed. Bulk prices for compost range from $13 per cubic yard for yard waste compost and $35 per cubic yard for food waste compost. Most compost facilities appear to be run by municipalities. The data I did find suggests that the industry is subscale. A 2016 analysis of New York City’s organic waste diversion notes that private waste carters picked up 672,300 tons of food waste from city businesses in 2012, but in 2015 there was only 105,500 tons of food waste processing capacity within 100 miles of the city, charging tipping fees of $40 to $65 per ton.

The secondary revenue streams that composting and anaerobic digestion facilities generate should support lower tipping fees than landfills charge, the challenge is collecting it in a way which optimizes costs and encourages additional investment in disposal facilities. This is where Quest adds value. By aggregating food waste amongst its customers, it can plan denser routes and lower the collection cost per ton. This in turn will encourage infrastructure investment, helped along by various sticks and carrots from governments looking to manage their rising landfill costs, and bring the all-in cost of these disposal alternatives below landfilling. Is this a flywheel?

Edit: Part 2 is now up!

Thank you for reading Part 1 on QRHC. Any questions or comments are welcome; subs and shares are greatly appreciated. You can also follow me @AmbroseKira on Twitter for more.