Disruption in Recycling Part 1

Let's talk trash, baby. Plastic trash. Recycling was upended three years ago and the solutions carry profound implications for business models, industries and value chains alike.

Welcome to Efficiencies, a blog situated at the intersection of strategy and sustainability, exploring all that relates to the business models and industry dynamics of the disruptors and the disruptees in our shift to the Green Economy. If you like what you read, please show your support with a free subscription or by sharing with a friend! Join the discussion and let’s grow this community.

A cornerstone assumption of modern investment theory is that companies will go on forever. It’s the terminal growth rate we use in our DCF models, where we plug in assumed GDP growth: 3%. The global economy has always grown, so it seems logical to extrapolate the past into the future. But what kind of future do investors underwrite when they apply a 3% perpetuity growth rate? It’s typically 2% volume growth and 1% real price growth. Volume can be anything, but in the case of physical goods it converges to one thing: trash.

Trash is a tougher problem to solve because our economic system doesn’t incentivize it. There is value in food that prompts farmers to improve crop yields but there’s no value in trash beyond removing it from sight. Recycling in its current form is an ineffective salve, yet continued exponential growth of trash is unsustainable. Developments in recent years suggest we’re approaching the limits of the planet’s capacity for trash. Despite this Waste Management (WM) trades at 37x earnings, suggesting the market views a disruption of our trash-churning status quo as a hypothetical. I don’t claim I can time it, but math and common sense tell me that decoupling trash from economic growth is an inevitability. Managing our environmental debt requires redirecting economic incentives in ways that carry profound implications for business models, industries and value chains that investors and entrepreneurs should seriously evaluate for opportunities and risks. That’s what this series aims to do – understand the ecosystem, economics, challenges and potential solutions of trash and recycling.

Plastics: the payday loan of environmental debt

Plastic is remarkably versatile. It comes in many colors, it can be flexible and sheer, or tough and opaque, some have been linked to cancer and developmental problems, and others are inconclusive. Because of its versatility, plastic is everywhere in our lives – our toys, our clothes, wrapping our single-use plastic disposables, lining the inside of our Starbucks cup – and it is remarkably tough. It can degrade, it can break down, but it will not decompose for thousands of years. If it does not decompose, where does it go? It goes in the ocean and in the soil as microplastics, it goes in the plants that absorb the microplastics and the animals that eat the plants, it goes in us1. Plastic has worked it way so thoroughly into our ecosystem that babies are born with plastic in them. If you’ve ever called someone plastic, realize that you are a pot calling the kettle black because we consume about a credit card’s worth of plastic every week. All the attributes that make plastic so economically attractive – versatile, cheap to produce, highly durable – make it the most abundant and difficult to recycle kind of trash.

A brief history of plastic

Given the environmental concerns we have today about plastic, it’s ironic that it got its start as an environmental savior of sorts. In 1869 John Wesley Hyatt invented the first synthetic plastic in response to a New York firm’s $10,000 offer for anyone who could provide a substitute for ivory, singlehandedly saving elephants from the West’s obsession with billiards.

Plastic is not one thing. It’s a category of materials called polymers, principally made from carbon supplied by fossil fuels. Leo Baekeland invented the first fully synthetic plastic, Bakelite, in 1907 to create a synthetic electrical insulator to support the rollout of electricity in the U.S. It wasn’t until World War II that the plastics age began in earnest. Consumption of materials was far outpacing what nature could provide (wood, glass, silk, etc.), so nylon, plexiglass and other new plastics stepped in to fill the gap2. Major chemical companies began inventing plastics for the sake of it and then sought out uses for them. Today there are thousands of unique polymers while global plastics production has compounded 8.5% annually from 1.5 million tons (MT) in 1950 to 348MT in 2017.

The first recycling programs appeared in the 1960s and exploded in the 1970s as landfills accumulated and environmental awareness spread. This continued through the 1980s when media attention was captivated by the plight of a Mobro 4000 aka “The Garbage Barge”, which spent months on the ocean looking for somewhere to dump its waste cargo. In truth, recycling was never an answer for plastic trash. The recycling participation rate peaked at 30% in 1998, but the amount of plastic that is actually recycled in the U.S. was 8.7% in 2018.

Recycling economics never worked due to the unchecked explosion in permutations that effective recycling would have to account for. There are too many types and combinations of plastic in various conditions in various channels for recyclers to effectively plan for and collect, let alone do it economically. In 1973, documents uncovered by NPR and PBS sent to top plastics industry executives acknowledged the issue:

“A report sent to top industry executives in April 1973 called recycling plastic "costly" and "difficult." It called sorting it "infeasible," saying "there is no recovery from obsolete products." Another document a year later was candid: There is "serious doubt" widespread plastic recycling "can ever be made viable on an economic basis."”

The Global Waste Trade

It begs the question, how does the recycling industry exist? The answer is the global waste trade. NIMBY-ism and tightening environmental regulation drove up the cost of landfilling in developed countries, prompting waste management companies to look abroad. Evolution of the global polyethylene waste trade system, published in Ecosystem Health and Sustainability, details the development of international waste flows:

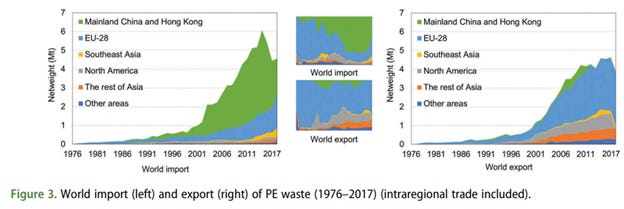

In the 1990s, as a wave of private market reforms kick-started China’s economic expansion, the country had a lack of quality plastic material to meet climbing domestic demand driven by its manufacturing industry and burgeoning middle class. China’s inclusion in the World Trade Organization in 2001 kicked off a dramatic increase in plastic waste imports from less than 10% of the global total in 1999 to 60% by 2003. Imports were further helped by rising oil prices in the ‘00s which made the price of recycled plastic attractive relative to elevated virgin prices.

There’s a general rule that as a person’s wealth increases, they demand a higher quality of living. The corollary is that they are also less tolerant of unpleasant things. I’ve never seen a country club downwind from a landfill. This rule holds for nations as well; as China’s wealth and domestic plastic production grew, it imposed stricter quality standards on imported waste beginning with the 2013 Green Fence campaign. At the beginning of 2018, China enacted its National Sword policy and banned the import of 24 types of solid waste and severely curtailed the allowable contamination levels on other types of materials. The effect was seismic – China went from importing 60% of the developed world’s plastic waste in the first half of 2017 to less than 10% in the first half of 2018. The National Sword bans hit recycled paper most acutely; U.S. prices for lower grade mixed paper fell to $0 in 2019 while pricing for higher grade old corrugated containers (OCC) fell from $71 in November 2018 to $22 in November 2019.

In truth, there was no magic that made recycling work in China when it couldn’t work in North America. Labor for sifting through the garbage for reusable plastic was cheap and enforced environmental regulations were nonexistent. The country had very permissive quality standards and a good amount of the plastic exported to China was burned for energy or discarded in open landfills.

China’s initial unwillingness to enforce quality standards on the plastic waste it accepted masked the worsening recyclability of the waste being exported and likely propped up an industry that was never anticipated to be economically viable. Waste Management CEO James Fish’s commentary in the first quarter 2018 earnings call is illuminating:

“Last year, the Chinese government decided that they were tired of importing increasingly contaminated recyclables. So they changed their policy to only accept recyclables with a 0.5% contamination content. Some of our plants see material come in the front door that is 40% trash. So we have to try and pull out almost 99% of that trash from the recycle stream in order to sell it to China as recycled commodities. Even our best-in-class inbound streams, which have only 10% contamination, still have to pull out 95% of the trash before they can sell it.

As diversion goals3 have increased, so too have our contamination percentages, which have increased from 10% to 15% 5 years ago to 20% to 25% today. In addition to that, China temporarily suspended import licenses, which caused global commodity prices to plummet last fall, and they have yet to recover.

Clearly, this is not a sustainable recycling business model. We must address higher operating costs in our recycling facilities and shrinking revenue from the sale of recycled products.”

In his commentary Fish places the blame for worsening contamination on consumers, but it should be shared. With no feedback mechanism to incentivize consumers to manage the quality of their recycling (such as a fine), the average person was largely ignorant of the problem. In turn, there was no pressure on packagers and plastics manufacturers to use plastic in a way that made recycling easier. In the instances were municipalities received economic pushback on the quality of recycling streams, they responded rationally by banning difficult to recycle plastics. Waste Management added this interesting bit in their risk section beginning in their 2018 10-K, the first annual report after China’s ban:

Additionally, with a heightened awareness of the global problems of plastic waste in the environment, an increasing number of cities across the country have passed ordinances banning certain types of plastics from sale or use. Bans on single use plastic bags, straws, and polystyrene food containers have been passed in over 350 cities, and a ban on single use plastic bags has been implemented in the State of California. These bans have increased pressure by manufacturers on our recycling facilities to accept a broader array of materials in curbside recycling programs to alleviate public pressures to ban the sale of those materials. However, there are currently no viable end markets for recycling these materials, and inclusion of such materials in our recycling stream increases contamination and operating costs and can negatively affect the results of our recycling operations.

A year later, the number of cities with plastic bans swelled to 585 and more forceful language was added in the 2019 10-K:

However, with no viable end markets for recycling these materials, we and other recyclers are working to educate and remind customers of the need for end market demand and economic viability to support sustainable recycling programs. With increased focus on responsible management of plastics, our procurement team has taken a proactive approach to ensure environmental sustainability goals are prioritized in managing the products we buy.

China’s ban set off disruption in the plastic value chain. There is now pressure to address the inherent mismatch in incentives between the recyclers, consumers, packagers and producers, which will be explored in part 2.

The tipping point for trash arguably occurred three years ago. Global trade flows of plastic waste in 2018 plummeted 45.5%. The U.S., which exported over half of its recycling in 2017, saw that percentage fall to ~34% in 2018 as exports to China and Hong Kong fell 82%. The ban sent shockwaves through the recycling industry, cratering recycling commodity prices or disappearing entire markets for lower volume recycled plastics.

The thing about compounding is it can quickly get out of hand – of the 6.3bn tons of plastic waste generated since the 1950s until 2017, over half was generated in the sixteen years between 2001 and 2017. Although smaller Asian countries saw their waste imports skyrocket in the aftermath of China’s ban, they simply were not large enough to absorb the amount of waste that China once did and instituted their own bans.

What a stunned industry thought was an infeasible announcement by China in 2017 seems to be the start of a secular movement. At the start of 2021, international shipments of plastic scrap and waste became regulated under the Basel Convention and 187 countries were theoretically banned from trading plastic scrap with the U.S.4

So here we have a perfect storm for innovation and disruption in the world of trash and recycling. Countries are putting up walls to foreign trash. The recycling industry, long propped up by China and never really functional, is breaking. At the same time, climate change initiatives to wean transportation and electricity from fossil fuels is turning oil and gas companies’ attention towards the plastics industry. It’s not the sexiest industry I’ve researched, but trash is fascinating.

Thank you for reading part 1 of the series on trash & recycling! If you enjoyed, please consider sharing with a friend or subscribing to catch part 2, which will dig into the changing economics of the recycling business and the implications for the value chain.

I will go on record here and bet that the next evolution of the organic eating trend will be plastic-free food. Investors, vertical farm marketing departments, please hit me up.

Source: Sciencehistory.org

By diversion, Fish means people throwing items they hope are recyclable into the recycling bin, thus diverting them from the trash

“Theoretically” because the U.S. is not a signatory to the Basel Convention and therefore should be banned from trading with signatories, but plastic waste exports actually grew in Q1 2021