Recycling Part 2: Structural Issues

Demand for recycled material is surging but there are structural challenges to increasing supply

Welcome to Efficiencies, a blog situated at the intersection of strategy and sustainability, exploring all that relates to the business models and industry dynamics of the disruptors and the disruptees in our shift to the Green Economy. If you like what you read, please show your support with a free subscription or by sharing with a friend! Join the discussion and let’s grow this community.

This is part 2 of the series on recycling and trash. Trash – particularly plastic trash – is an environmental dilemma that exists at the intersection of our aspirations for exponential growth and the limited capacity of our planet, only a few years behind climate change in capturing the public conversation and upending established industries. This is an incredibly complex ecosystem and what follows is a high level analysis focused on consumer generated plastic waste. Future newsletters will dig in deeper with stock-specific analysis. In part 1, we reviewed the explosion of plastic that occurred in the mid 1900s, the global waste trade that masked the inherent brokenness of current recycling programs and the 2018 ban by China that catalyzed the greatest disruption that no one is talking about. Let’s talk about it.

What is trash?

In economics there are a few unusual types of goods that violate the basic laws of economics. A Veblen good, for example, is a luxury good for which demand increases as the price increases, resulting in an upward sloping demand curve. I consider trash another kind of unusual good because has a negative price – people pay to remove it. It’s the antimatter of economic goods, or possibly an economic black hole, sucking value out of anything it comes into contact with. Consider that high volume landfills decrease adjacent residential property values by 12.9% on average, with each mile between the home and the landfill reducing the impact by 5.9%.

Trash is loosely comprised of eleven categories:

Which are managed in one of four different ways:

The difference between trash and recycling is that trash cannot be made into anything of value. Ideally, everything but food and yard trimmings would be recycled, while organic waste would be composted. Everything would maintain a positive inherent value and there would be no true trash. This is the vision for a circular economy that environmentalists posit.

It makes sense as a concept, but in practice there are technical and structural implications to discuss. I’ll try to balance the discussion of the minutiae and the big picture because I think that’s where the value add is here; the sources discussing the engineering challenges don’t acknowledge the structural challenges, and vice versa.

The Technical

The chief challenge to plastics recycling is complexity. Closed-loop recycling, where plastic material is infinitely recycled into equal quality material, requires homogeneity and simplicity. That’s not what we have.

A plastic is either a thermoset or thermoplastic. Thermoplastics (~2/3 of global production) have a much better chance to be recycled, with PET having one of the highest recycling rates at ~30%. Thermoset plastics are much more challenging to recycle because they cannot be re-melted and reformed. Within these two groups are subcategories such as PET, PE and PP in thermoplastics. Why does this matter? They cannot be mixed, at all. Per Plastics recycling: challenges and opportunities:

“A major challenge for producing recycled resins from plastic wastes is that most different plastic types are not compatible with each other because of inherent immiscibility at the molecular level, and differences in processing requirements at a macro-scale. For example, a small amount of PVC contaminant present in a PET recycle stream will degrade the recycled PET resin owing to evolution of hydrochloric acid gas from the PVC at a higher temperature required to melt and reprocess PET. Conversely, PET in a PVC recycle stream will form solid lumps of undispersed crystalline PET, which significantly reduces the value of the recycled material.”

In plain speak, this means the first step towards proper recycling requires sorting your plastics by the seven labeled types numbered on recyclables, with the seventh category “Other” being a big catch-all. Plastic food packaging also needs to be cleaned to remove organic waste.

But wait! That’s not enough. Plastic packaging frequently uses multiple types of polymers and other materials like metals, paper, color additives and adhesives that improve performance but contaminate the recycling stream. Most consumer goods utilize multi-layered packaging, which is not readily recyclable because it is impossible to separate and sort the layers. There’s nothing that you, the consumer, can do about this.

Even within polymers of the same type, there could be differences in molecular weights (to suit the intended manufacturing process of the end product) that make them incompatible to be recycled together.

As a result, most plastic isn’t recycled into plastic of equal quality and is either thrown out or downcycled instead. PVC recovered from plastic bottles may become traffic cones; mixed plastics can be made into plastic lumber used for industrial flooring and park benches. Downcycling delays plastic ending up in the trash but does not prevent it.

This is far from a comprehensive discussion of the technical challenges facing recycling; it’s merely trying to illustrate how complex and heterogenous the plastic waste stream is by the time it reaches the consumer. This is extremely problematic because (1) the majority of plastic ends up in the consumers hands between packaging and consumer goods and (2) these end-uses have the highest turnover.

If recycling could be dramatically improved by simplifying the plastic waste stream, why haven’t we done so?

It comes down to incentives. Simplification is a gentler word for commodification, which is another way of saying “no excess profits”. All firms are incentivized to maximize their profits and the top of the plastic value chain is no different; they’re incentivized to make the waste stream heterogenous. Plastics producers make money selling new plastic; if half of the plastic they sold each year was recycled in a closed loop, they just lost half of their revenues. They don’t own the collection or recycling infrastructure. Packaging companies earn higher margins on specialty and multilayer material. Manufacturers benefit from cheap material and from differentiating their products with incremental variations and flashy packaging, a strategy they tend to stretch past the point of diminishing returns:

“Many companies leverage expanding product offerings as a company strategy. Harvard Business School Professor Clay Christensen asserted that 30,000 new consumer products are launched yearly. However, studies have found that there is a disparity between the number of new products and the growth of revenue within a firm. According to a report from BCG (Pichler, Dawe, & Edquist, 2014), new products introduced annually from 2002 to 2011 grew by 60%; however, the company’s sales grew just merely by 2.8 per year.”

The burden of recycling is placed on the end consumers – an extremely fragmented and heterogenous group. The more fragmented a group is, the less bargaining power they have. That’s why consumer boycotts are rarely successful. Unfortunately, the group with the least clout is on the receiving end of the economic consequences. For years, China’s low quality standards masked the higher cost of proper recycling. With the ban on plastic waste imports, U.S. recyclers have restructured their recycling agreements with customers to pass along the higher costs. The difference isn’t insignificant – my town of Stamford was paid $95k for its recycling in 2017 and in 2018 had to pay $700k for its recycling to be removed. In response, cities (including Stamford) have introduced local bans on single use plastics and Styrofoam. But other have canned their recycling programs altogether; it’s hard to blame them when most of the recycling will be sent to the landfill anyways.

Real change requires the proper alignment of incentives; it’s unfair and fragile to ask just one group in the value chain to ignore their incentives or subsidize another group while everyone else is allowed to indulge. In this case it’s asking consumers to bear the costs of recycling or expecting one snack manufacturer to pay for more expensive recycled material while others don’t. The best way to address the incentive problem (in my opinion) is by setting minimum recycled content standards. This doesn’t prescribe a solution (which is incredibly difficult for a material as widely used as plastic), it mandates an outcome and lets the market figure out the best solution(s). By creating forced buyers for recycled material, manufacturers will purchase packaging from the supplier that offers the best cost, incentivizing packagers to invest in R&D to bring down the cost of recycling, organize supply chains to effectively source recycled content and make their products easier to recycle with an eye to increasing future supply.

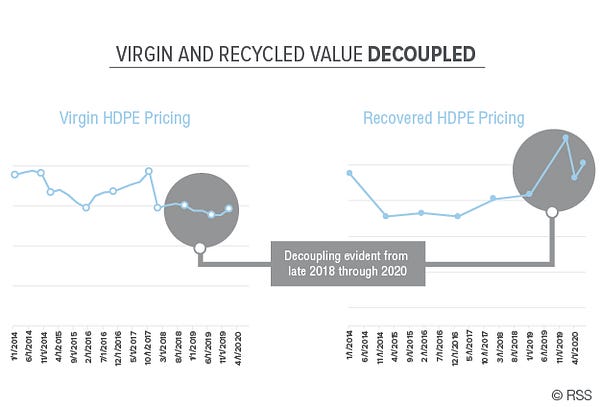

Post-consumer content targets have been set in the E.U., certain U.S. states and by large consumer goods companies, sharply increasing demand for a material that’s thinly supplied and completely price-inelastic due to its lagged, indirect production. If you want recycled PET (R-PET) today, you needed to make recyclable products last year and hope they were properly disposed of and collected. As of February 16th, 2021, the average price of R-PET containers had increased 30% YTD, while post-consumer polypropylene prices increased 58% month over month. With many major customers and governments mandating step-ups in minimum recycled content in 2025 and 2030, demand is likely to outpace supply for a long time. I look forward to an R-PET ETF in the near future.

In under two years, plastic waste has gone from trash to a valuable commodity. With this shift will come a transformation of collection and recycling infrastructure. I expect we’ll see more M&A like the acquisition of RPC Group, one of Europe’s largest plastics recyclers, by Berry Global Group, a global packaging company, as packagers work to secure supply in recycled plastics, as well as consolidation among plastics recyclers. There will also be innovation in plastic waste collection, because as Steve Alexander, president of the Association of Plastic Recyclers, puts it:

“Each of the thousands of communities in the U.S. collects different types of materials, so there’s no consistency from one system versus the other. That’s a significant issue.” Alexander estimates recyclers will need to collect more than four times more plastic by 2025 than they are currently collecting, but “asking the current infrastructure to generate the potential feedstock for recycling that the brands have indicated they want is like asking a 1978 Chevrolet Chevette to meet current California emissions standards.”